When I began steelhead fishing back in the early 90’s, the primary fly fishing method in Great Lakes tributaries was mostly chuck-and-dunk. A fly was tied about eight-inches behind enough weight to sink it to the bottom of the river and the fly was “ticked” along the gravel in current seams. Egg patterns, spring wigglers and egg sucking leeches were the most popular and productive flies of the time and responsible for taking the majority of fish. This method and the flies that were used were very different than west coast methods and developed specifically for Michigan’s tributary rivers.

On the opposite side of the lake, Wisconsin’s tributary streams are vastly different. Wisconsin rivers are significantly more shallow, there are more boulders, less gravel and silt is more prevalent than sand (due to agricultural run off). The rivers are small – in width and river miles to the first damn. Fish hold in water less than two feet deep and you’d be hard pressed to top your waders during normal flows in all but a few places along these rivers. In short, it’s an entirely different ball game compared to both Michigan Steelheading and the Pacific Northwest.

For me, ticking along the bottom was an exercise in frustration — the sheer numbers of large rocks on the river bottom create an absolute mecca for snags. Don’t get me wrong, there are anglers who employ deep-water methods and catch fish. They wade into the shallow water near choke points and spook the fish into the tailouts of riffles – where three to four anglers will camp a foam line until the cows come home. They catch fish. They appear to be happy. Who am I to judge?

As a hard-core, down and across fisher of wet flies for all things trout, chunking lead just wasn’t going to work for me. I just didn’t see the sense in making my life difficult to get a fly to swing two feet below the surface for fish I could site cast to all along the river.

In the days before the spey craze, when sink tips were also in their infancy, I experimented with everything from lead-core fly line to sink tip extensions. From weighted flies to twist on lead, long leaders and short, I tested every combination to get a fly to sink quickly and swing snag free in confined spaces. As I mentioned, large rocks litter the river bottom in most pools and riffles. Current speeds differ greatly from riffles to tailouts and I knew finding an all-purpose solution would be difficult at best. After seasons of trial and error, I arrived at a solution: lead-wrapped sink tip extensions (which I still use today).

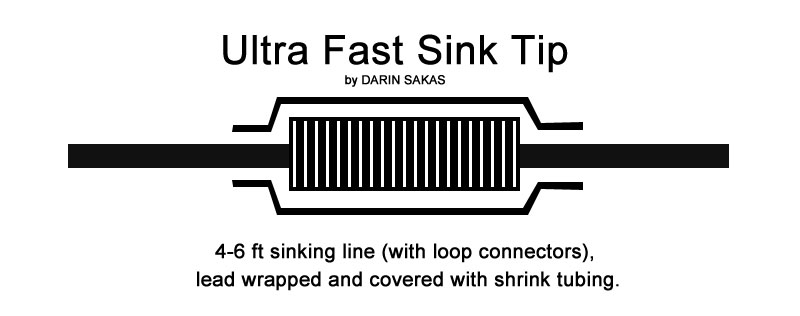

Constructing these specialized sink tips is quite easy. Using a 4-5 foot section of ultra-fast sinking line, affix loop connectors at both ends. On the tail end of the extension (using varying gauges and lengths of lead wire or solder) spiral a length of lead wire around the line (as you would cover a hook shank) then cover the lead with a small section of shrink tubing (from any electronics store).

I construct a variety of lengths and weights to achieve my desired sink rate for changing current speeds or swing obstructions. When large boulders block the path of a slow sink swing, I switch to heavier tips and add often add weighted flies. Changing the specialized extensions is fast, easy and, in my humble opinion, are much more elegant and productive for my style of fishing.

In addition to depth control, I find this rig allows for a considerable amount of line manipulation when control the speed of the swing. Lets face it, you can’t mend line under water and the short length allows floating line to be controlled as well as typical down and across, wet fly presentations.

I have used these custom sink tips with success on everything from salmon to brown trout (with streamers) in water depths nearing six feet. While it will really give your shoulder and arm a workout on streamers, it works when you need to dig deep for fish, or get down fast in a swift current.