The longer I fish the more I’ve realized there is always a trout willing to prove me wrong. I suppose if I always had their number, the pursuit and hopeful success would be far less grand than it is today.

In the game of catching trout, presenting the right fly in the wrong manner will produce the same results as fishing the wrong fly. While there are days on the river when the bug that is hatching is both visible on the water and in the air, there are those evenings when you see rising fish in the absence of any apparent insect activity and the ‘obvious’ offerings just don’t work.

Both Sulfurs and Hendrickson nymphs are extremely active in the days and hours before emergence. Not only do they migrate to preferred staging areas for hatching, they are reported to make “practice” runs from the stream bottom to the surface and back prior to any real emergence. This behavior can actually begin days or even weeks before a hatch occurs.

In the slick pools above the riffles I have witnessed this phenomenon – trout rise with consistency on water void of insect activity and only the hump of their back or a tail breaks the surface.

As an avid wet fly fisherman I normally categorize these subsurface feeders as easy targets. I fish subsurface and they are feeding subsurface, it shouldn’t get any easier, right?

I fish, I swing, I change flies and even dead drift various soft hackles. Yet nothing. Even a nymph dropper doesn’t get so much as a bump.

After an hour of fishless fishing I retreat to the bank for a bit of observevation. I quietly stalk upstream and each step of my wading boots awakens a feeding frenzy of mosquitos from lush ferns – as if the evening had not been painful enough already.

I perched myself on a tall bank near a few risers and watched intently as they gently drifted backwards downstream and barely opened their mouths to eat something, then rocketed back to their feeding zone with a flick of the tail.

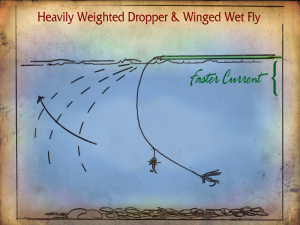

It became apparent I needed a deep drift and a slow rise from the bottom to take these fish. Returning to the river I changed my point fly to an all-purpose orange, silk-bodied, winged-wet fly (which appears translucent amber when wet), then switched the dropper to a ultra-heavy, lead-wrapped and bead-headed nymph.

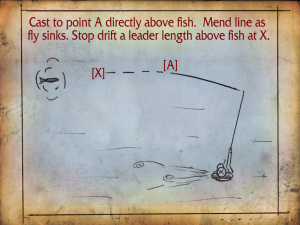

I waded out and positioned myself well above a rising fish – that was no more than a rod length to my side. I made a short cast directly above the fish and mended line down to the fish as the team of flies sank towards the bottom (fig #1). From my observations I knew the fish would be at least a yard above the rise form. When my fly line was a leader length away from the suspected holding spot, I put the brakes on held my rod tip high (figure #2). I did not lift the team of flies as you would using a Liesenring lift because I felt as though it would add too much speed to the rising flies. I simply let the current gently roll my wet fly towards the surface and it was met with a deep, hard strike.

Twenty fish later, I decided to back test my theory. I set up a nymph rig and fished it to a number of rising fish. From dead drift to lift, this presentation only took one fish out of a dozen risers and countless casts.

In the case of swinging wet flies and soft hackles, then dead-drifting nymphs, the standard presentations were incapable doing what the trout wanted. The fish wanted insects that rose in front of their noses near the stream bottom. While an expert nymph fisherman maybe be able to simulate this presentation better than I, the method of “cast, mend, mend, mend, put on the brakes” ultimately offered greater control for me and the fish approved.

The next time you are faced with picky fish that are rising to bug-less skies – dig deep and put it in their face.